|

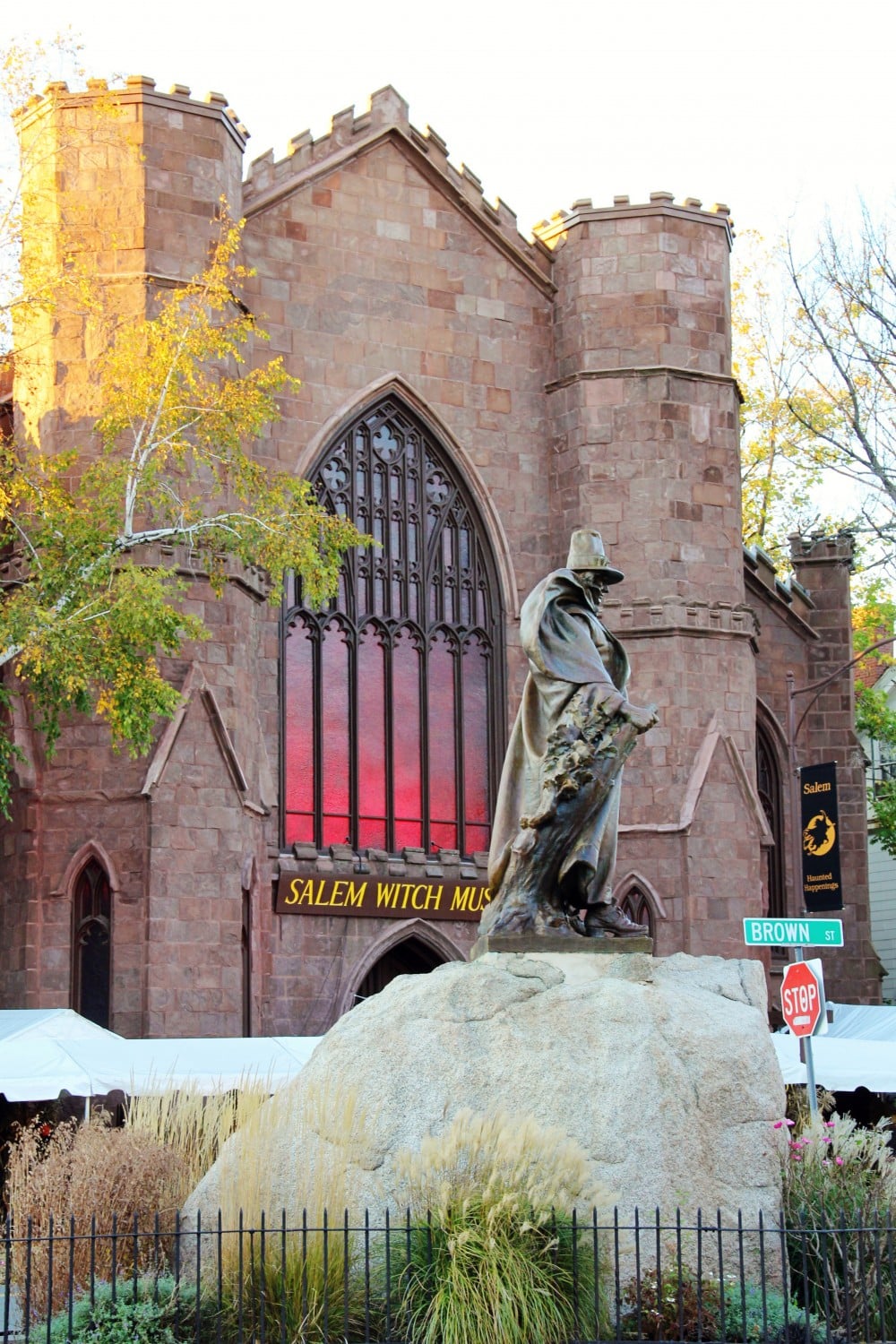

| The Salem Witch Museum at night. |

The town is not only a living piece of early American history, but it also hosts one of the most brisk tourist attractions on the East Coast. Here is an account of how Halloween is spent in Salem.

Halloween in Salem, Massachusetts

In the mood for a good scare? Consider spending Halloween in Salem, the witch capital of New England.

Alyson Horrocks • October 8, 2016

|

| A statue of Roger Conant, the founder of Salem. |

The witch trials of 1692 cast a shadow over Salem, Massachusetts, that has spanned centuries, seeping into the city’s collective consciousness and shaping its character. Yet what was once only a source of infamy for this historic coastal city is now a highly profitable tourist draw. For the most part, Salem’s status as “Witch City” has been embraced, or at least tolerated, by those who live here. But for visitors, it’s downright fascinating — and never more so than at the spookiest time of year. Here’s a look at my experience of Halloween in Salem.

At the city’s annual month-long Halloween festival, Haunted Happenings, events kick off with a grand parade in early October and come to a close with fireworks display over Salem Harbor on Halloween night. In between are Halloween-themed theatrical productions, carnival rides, psychic fairs, haunted attractions, costume balls, and more. Haunted Happenings lures thousands of tourists to the city, many of whom don colorful and festive witch hats.

But while I enjoy the festival’s aura of spooky fantasy and fun, I begin my own experience of Halloween in Salem at the Witch House on Essex Street, getting reacquainted with the real tragedy that occurred in this town back in the late 17th century. Despite its name, this landmark building wasn’t the home of a witch, but rather it belonged to the wealthy and upstanding Corwin family — most notably Jonathan Corwin, one of the magistrates responsible for investigating the allegations of witchcraft and sentencing the accused.

|

| The Witch House, home to Jonathan Corwin, one of the judges in the witch trials. |

Thought to have been built in the 1660's, the Witch House is not only a stunning example of early New England architecture but also an intriguing link to the witch trials. Each room features information and displays highlighting the Corwin family, witchcraft, and the history of the trials.

One of the Witch House artifacts that draws me in is a 17th-century poppet. Poppets were simple, even crude, dolls that many in colonial New England believed to have mystical powers. As with voodoo dolls, it was thought that what you did to a poppet would be felt by the target of your malice; anyone found in possession of one of these dolls would almost certainly be suspected of witchcraft. During the witch trials, the discovery of poppets was testified to in court and played a role in the downfall of the first person to be executed, Bridget Bishop.

|

| A 17th Century poppet. |

After getting a fascinating lesson on politics and history at the Witch House, I find the human tragedy of the witch hysteria brought into sharp focus at my next Halloween-in-Salem stop. Dedicated in 1992, on the 300th anniversary of the trials, the Salem Witch Trial Memorial sits next to the old Burying Point Cemetery. The memorial features granite benches bearing the names of the 19 people who were hanged and one who was pressed to death. The victims’ chilling pleas of innocence are carved into stones at the entrance to the memorial.

|

| The memorial bench of one of the first to be executed during the trials. |

The Burying Point, next to the memorial, predates the witch trials by several decades, but don’t look for the victims’ headstones here. According to Puritan belief, those found guilty of witchcraft were in league with the devil and could not be buried in consecrated ground. The final resting places of almost all the witch trials’ victims remain unknown. (However, one of the judges from the witch trials, John Hathorne, is buried here.)

|

| The Burying Point. |

After a visit to the Witch House and a stroll through the memorial and cemetery, I feel I’ve gained an understanding of the true historical events of the past — and now it’s time to explore the spooky, carnival-like atmosphere of today’s Halloween in Salem. The transition from serious history to celebratory fun isn’t hard to make: As soon as I step out of the cemetery, I am greeted with the smells of fried dough, apple cider, cinnamon buns, and other festival food. Fog machines pump clouds through the narrow streets as displays of skeletons, witches, ghosts, and monsters entice visitors to various attractions.

|

| A street attraction in Salem. |

Meanwhile, Salem’s historic cobblestone streets are filled with vendors selling kitschy souvenirs, makeup artists offering gruesome makeovers, and costumed monsters posing with tourists. Providing a dramatic backdrop to the Halloween madness is the world-renowned Peabody Essex Museum.

|

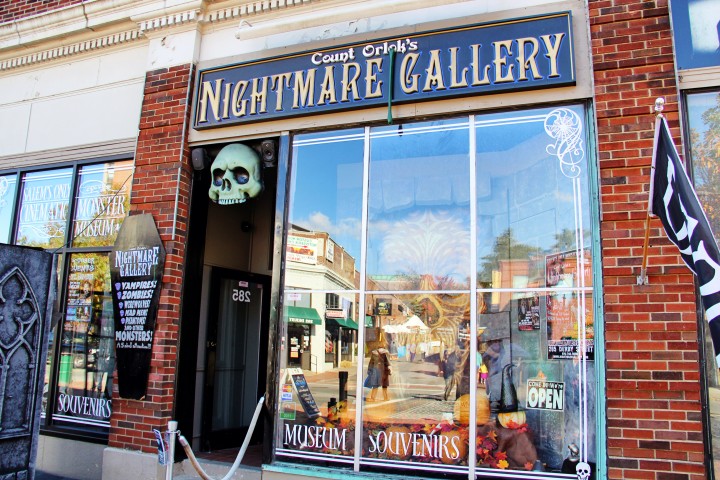

| One of the numerous shops catering to tourism in Salem. |

|

| "I got stoned in Salem, Mass." |

BONUS: Interview with Stacy Schiff, Author of The Witches

Brenda Darroch • November 12, 2015

Stacy Schiff is a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer whose latest book, The Witches, examines the many mysteries and misconceptions about the Salem Witch Trials. I caught up with Stacy at The Music Hall in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to learn a bit more about the challenges and surprises she encountered during the four-and-a-half-year process of compiling and chronicling historical data in her quest to illuminate New England’s darkest hour.

What drew you to the Salem witch trials?

So many things. It’s this spectacularly strange moment, so we go back to it over and over, but we tend to go back to it with a lot of misconceptions. So it’s sort of a touchstone. Everybody knows the Salem witch trials, but no one seems to know much about them, or what we know we’ve taken from Arthur Miller. So we have this rather vague idea that we burned witches, and it was men accusing women. Nobody knows there were male victims, a minister hangs, or that it all takes place over nine months. The basics of the story have been misshapen over the years.

It’s a fascinating moment in that it’s so not what we think about America. Here we are in this idyllic Bible commonwealth, and we don’t think about ours as the kind of country where we persecute innocents. And then you have the whole female angle. After Cleopatra, I was looking for something where women’s voices play a lead role, where women are somehow the driving force behind the narrative.

What were the young women whose accusations fueled the witch trials experiencing?

Some of them were expressing legitimate pain. Yes, people think these were just bratty adolescents, but those first afflicted girls were trying to express something they couldn’t put into words. So you have very piercing, articulate women’s voices here, but then you have a suffocating sense of something that can’t be spoken, that we can’t actually decipher, but is very powerful.

What was your biggest challenge when approaching this project?

There’s so many answers to that, but there were three hurdles that come immediately to mind.

One is that you don’t have the girls’ voices; no Puritan girl leaves a diary. And that’s one of several holes in the record. Documentation-wise, 1692 has gone missing in so many ways. It’s missing from sermons. It’s missing from collections of letters. It’s missing from diaries. We don’t have the court papers. There’s this complete lacuna at the center of the story.

Another problem is that narratively you can’t write about every one of the people who was a victim, because it’s already a huge cast of characters. So you have to pick and choose who you are going to write about. And it took some time for me to realize that the ones you write about are the ones who carry the story forward.

The third thing is you have to make something that’s crazy seem sane. Narratively, that means you have to buy into this completely hallucinated event. So when people say they’ve flown through the air, somehow you have to actually believe them.

How do you start the process of writing a book like The Witches?

I tend to immerse myself completely. I’ve read more of the secondary literature of this case than I have in other cases. I read anything that anyone wrote in the 17th century, although I didn’t read every 17th-century sermon, because you can’t. I read every diary, I read all the court papers that you can get your hands on from Essex County. And then once you begin to get a sense of the stresses and the climate, you can begin to see where the story’s going. There was a narrative high-wire act where I would realize, “Oh, wait, everyone’s accusing everyone else of witchcraft, so I guess I need to explain what a witch is.” Because, of course, the reader’s thinking witch — pointy hat, Margaret Hamilton — but that’s not what we’re talking about here. We’re talking about someone in league with the devil.

There was a conscious act of not wanting to deliver answers too early. So unlike any other book I’ve written, there was a need to have things come later, because otherwise I would have risked tipping my hand too early. I wanted it to read like a thriller where you sort of get it before it’s over.

As you were researching the witch trials, what surprised you the most?

So many things surprised me. I didn’t know anything about the political context, which played such a huge role here. The parallels between this Anglican invasion of Red Coats and this diabolical invasion of red-pen-toting devils. It’s such a similar set of images. I was surprised by how a simple case of witchcraft blossomed into this huge, political conspiracy to subvert the state.

I’m surprised by who the heroes are. It’s not who you think it’s going to be.

I’m surprised by the return to normalcy. How do you go back living next to the daughter who accused you or listening to the minister who accused you?

And I was surprised by the modern resonances. We don’t explain the world in the same way, but we do experience the same anxieties that these people were suffering from. We just explain it differently. As much as these people were living in a very different world from ours, what irritates them and what unsettles them isn’t all that different from what unsettles us.

[SOURCE: Yankee Magazine]

No comments:

Post a Comment